The ring and the widow’s mite

-

Msgr. Doug Doussan is 90 now, but his 20-year-old memory of the second collection at St. Lawrence of Brindisi Church in the Watts section of Los Angeles a few weeks after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 is proof of the presence of God through the work of human hands.

With television images after Katrina showing 80% of the city of New Orleans under water, hundreds of church parishes across the United States rushed to take up second collections to provide whatever immediate aid they could to a drowning city.

St. Lawrence was an inner-city church of 3,000 families – about 80% Hispanic and 20% Black. Their pastor at the time, Franciscan Father Peter Banks, characterized his parishioners as people of “very modest means.”

Most weekends, the St. Lawrence collection amounted to about $6,000, but on that weekend in September 2005, the second collection alone for Katrina relief came to $7,000.

Plus one stunning, anonymous gift.

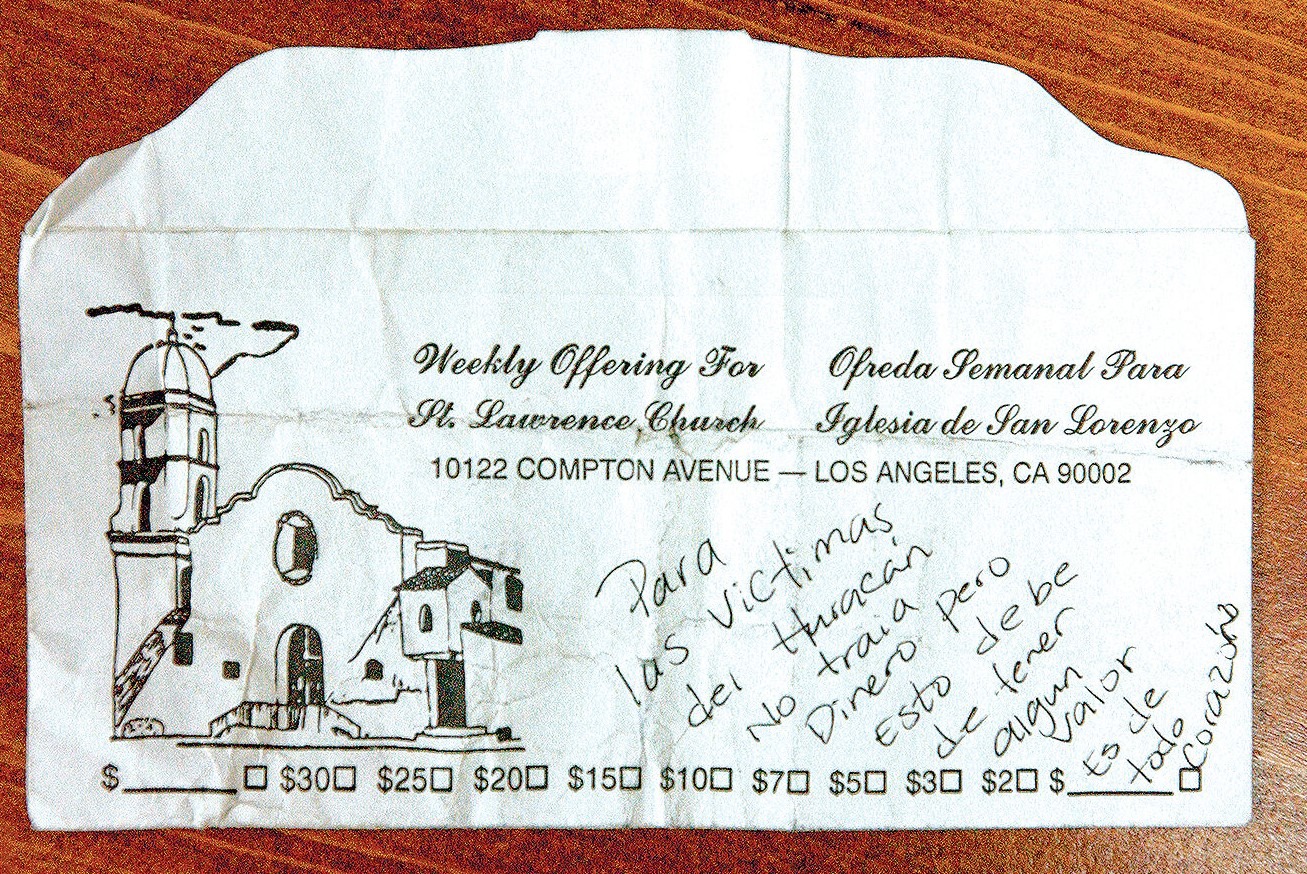

When the money-counting team gathered that Monday at St. Lawrence, they came to Father Banks and showed him a church donation envelope with a message handwritten in Spanish: “Para las víctimas del huracan, no traia dinero pero esto debe de tener algún valor. Es de todo corazón.” (“For the victims of the hurricane, I did not bring any money. But this should be of some value. It is with all my heart.”)

When Father Banks opened the envelope, he saw a gold wedding ring with small notches on the outside.

“My immediate reaction was, what incredible kindness and charity this woman had,” Father Banks said. “This woman had nothing, and she reached down on her hand and took off her ring. It reminded me of the story of the Widow’s Mite (Mark 12:41-44). This ring had to be very near and dear to her. This was all she had, and she gave it with all her heart.”

With the 20-year anniversary of Katrina fast approaching, Msgr. Doussan, the former pastor of St. Gabriel the Archangel Parish in Pontchartrain Park, says the parable of the ring remains one of the touchstones of his priesthood.

He attempted to find the woman who had donated the ring so that he might give it back, but he was never able to locate her. Instead, he had the ring and the collection envelope placed in a small shadow box as proof to his parishioners about God’s goodness in the face of despair.

A model of faith

A model of faithIn a way, the woman’s generosity mirrored the volunteer efforts of hundreds of people from far flung states to travel to New Orleans at their own expense to gut houses and put people’s lives back together.

As Msgr. Doussan reflects on Katrina – and the church his parishioners rallied to save without the benefit of any archdiocesan insurance money – he sees the miracles that can happen when people are empowered to keep their dreams alive.

“I was feeling positive that we were going to put this place back together because the people were so much in love with the parish,” Msgr. Doussan said. “We had to put it back.”

Some of his best friends – especially priest friends – thought he was tilting at windmills. Homeless for several months after Katrina, Msgr. Doussan took up residence with a good friend, Father Tom Ranzino, the pastor at St. Jean Vianney Church in Baton Rouge.

Msgr. Doussan was 71 at the time, and he was telling Father Ranzino about his staff, which included Sisters of St. Joseph Kathleen Pittman and Margaret Maggio, who were coordinating efforts to locate parishioners, help them gut their homes, and marshal hundreds of volunteers who came from New York, Ohio and California to do clean-up work. The parish even made an arrangement with a building materials company to provide Sheetrock to anyone who needed it.

“It’s amazing that they came and stayed where we had to put them – on the second floor of our school building – because it was completely horrible,” Sister Kathleen recalled. “We cleaned it up as best we could, and these volunteers came with their own sleeping bags.”

Hot meals – and church

Sister Margaret said after the church was cleaned out, there was enough room for “a crew of ladies” to prepare and serve meals every day inside the church.

“When you walked in, it was like a cafeteria,” Sister Margaret said. “So, you sat and ate on one side, and then you went to church on the other side. It was just an incredible experience of generosity. Those people left their homes and their jobs at their own expense and stayed here for a week to help us. They weren’t staying in the Hilton Hotel.”

Father Ranzino would hear Msgr. Doussan relate his stories of recovery in action – with the finish line shrouded by fog – and tried valiantly to provide his friend with a double dose of reality.

“Tom said to me, ‘Doug, I’m going to tell you this and you’re probably not going to want to hear this, but I have to tell you,’” Msgr. Doussan recalled, laughing. “‘How old are you now? 71? Why do you want to go back? Doug, this is going to take a long time, and it’s going to be hard work. You have all those buildings you have to deal with – the church, the gym, the rectory, da-da, da-da. There’ll be no end to it. You’re 71 – not 18 or 32. You’re going to run out of energy quick. Why would you want to stay?’”

A very tempting offer

Then Father Ranzino went to his closing argument, almost as if he were dragging Msgr. Doussan to the top of the temple to show him all the worlds that might be his – if only he listened to reason.

“He said, ‘You know, Doug, if you resigned, the archbishop would let you have a small parish, a place that would be real easy, maybe with a deacon, and you wouldn’t have too many people. You’re 71, and you’re supposed to retire at 75, and that’s only four years away! You don’t even know how successful it’s going to be,’” Msgr. Doussan recalled.

From the top of the temple – with the earth and all its kingdoms laid out before him – Msgr. Doussan essentially decided to cast his lot with the people of Pontchartrain Park.

And, they did reopen the parish, without the benefit of a penny of archdiocesan insurance.

“I told Archbishop (Alfred) Hughes we were determined to stay open,” Msgr. Doussan said. “I didn’t want to close, and the people didn’t want to close. They were already coming back. I mean, these were people who had been living here their entire life, so they weren’t ready to give up for a little hurricane.”

One of the lessons he learned as a priest, Msgr. Doussan said, was to empower his parishioners to assume major roles in the church as part of their baptismal call. His decision to offer continuing religious formation to dozens of parishioners at Loyola University and other institutions showed how seriously he took lay involvement in the church.

Ultimately, it was the reason St. Gabriel survived Katrina.

“We were convinced that there had to be real equality in the church,” Msgr. Doussan said. “There was no reason why a priest was supposed to know more about theology than a lay person. They were all, equally, members of the body of Christ. So, we started sending lay people off for studies so they could be leaders in the parish. Lay people could be in charge of some of the ministries because we didn’t have a lot of sisters and priests anymore. We needed to train the lay people. We’ve told them a thousand times – ‘You are the church. You are not the priest’s little pet.’”

As he ponders the approaching 20th anniversary of Katrina, Msgr. Doussan prefers to recall the rainbow and not the flood.

“I remember being amazed by two things,” he said. “One, the parishioners doing extraordinary things to come back and help the parish. And, two, the people coming from all over the country to help us. That was simply incredible.”

One woman couldn’t buy a plane ticket, but she dropped her wedding ring in the collection.